Email: rehiz_nk@knuba.edu.ua

Revised 26 January 2022

Accepted 25 November 2022

Available Online 10 January 2023

- DOI

- https://doi.org/10.55060/s.atssh.221230.023

- Keywords

- Traditional settlement

M'zab Valley

Kryvorivnia village

Revitalization

Tourism - Abstract

This article is devoted to the comparative study of revitalization and popularization experience of ancient settlements preserving a traditional way of living. The cases of geographically isolated desert settlements of M'zab Valley in Algeria and Ukrainian mountain village Kryvorivnia are examined. M'zab settlements are conservative in respecting millennial customs of social coexistence, including the field of architecture and urban planning. Tourism is developing there in a controlled manner, managed by the organization of local volunteer guides. Kryvorivnia invites tourists to participate freely in the local life, rituals and festivals. In both cases, the initiative of revitalization comes from local communities. The preservation of ancient culture and architecture of the settlements is based on their historical integration in the natural environment determining both the necessity and the possibility of the sustainability of local traditions.

- Copyright

- © 2022 The Authors. Published by Athena International Publishing B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

The theme of traditional settlements revitalization is an interesting aspect of the global question of their preservation. Such settlements are now quite a rare phenomenon when it does not concern “open-air museums of traditional life”, but real-life settlements fully preserving their historical atmosphere. Mostly they are settlements hidden in deep nature with some geographic features cutting them off from “the big world” that provokes there the effect of a specific “time delay”. At the same time, under modern globalization circumstances it became clear that such settlements cannot be completely separated from the world and inevitably have to communicate, whether finally dissolving their identity or consciously making efforts to preserve it. The most simple and effective way could be diversity of revitalization methods as well as development of local tourism. These activities are usually the point of local community interest aiming to vitalize local life and emphasizing the cultural significance of their settlement by registering it as Historic and Cultural Heritage.

In this article, an effort is made to analyze and compare experiences of revitalization and tourism development in the cases of M'zab Valley deserted settlements in Algeria (UNESCO World Heritage) and Kryvorivnia deep mountain village in the Ukrainian Carpathians. The work was conducted mostly with field research methods including the observation and fixation of local revitalizing and touristic activities, as well as interviews with participants of the process.

2. M'ZAB CASE

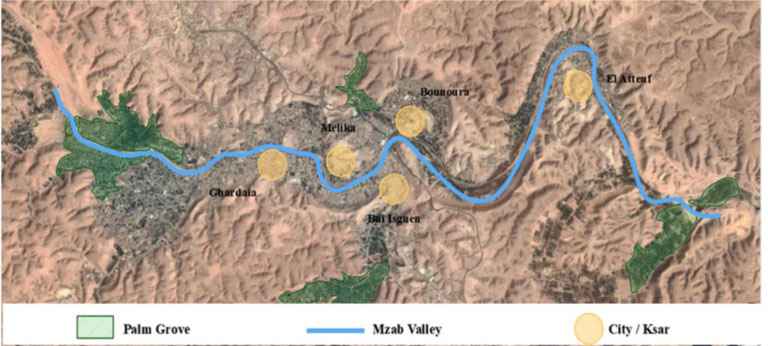

The M'zab Valley is a natural region located in the northern Algerian Sahara, in the province of Ghardaia, 600 km from the capital of Algiers. Ghardaia is famous with a network of ancient millennium cities, especially the five cities of pentapolis: Ghardaia, Melika, Beni Isguen, Bounoura, and El Atteuf (Fig. 1). They gathered in agglomerations along the M'zab Valley for political, commercial and military reasons, and were created between 1013–1355 by the Ibadites.

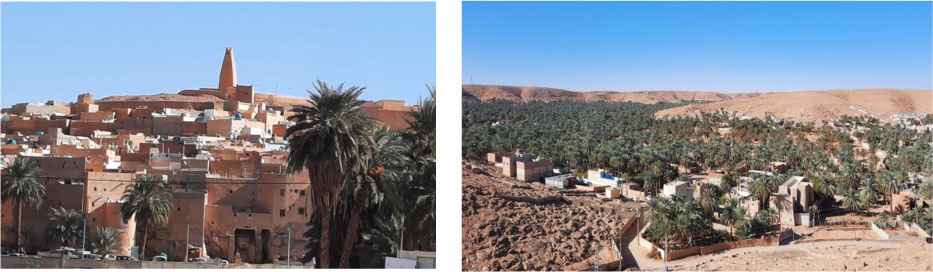

The landscape of M'zab Valley formed around the five fortified cities that have enchanting engineering characteristics designed with great skill in an exquisite architectural form (Fig. 2). They are built on rocky sites in adaptation to the arid desert climate due to optimal use of local building materials and the special orientation of buildings to take advantage of sunlight and ventilation as well as according to the Islamic religious rules. Each city (so called ksar) is a closed little world consisting of a group of adjacent dwellings and narrow alleys that form a harmonious urban fabric following the topography of the plateau. Where the mosque occupies the highest peak of the ksar, declare its sanctity and its leading role.

The five cities are surrounded by ramparts of 4–5m high equipped with gates and watchtowers along its length and have market squares (souk) located near the gates to facilitate foreign economic exchanges between the inside and outside of the city. Behind the ramparts, the oases spread out along the course of the valley and cemeteries include vast areas with chapels used for funeral prayers and teaching the religion.

The five historical cities of M'zab Valley (drawn by the authors).

Left: Ksar Melika. Right: the oasis of M'zab Valley (photos by the authors).

The architecture in M'zab Valley is simple, but functional and integrated into the environment. It is designed for communal living, within an egalitarian social structure that respects the privacy of the family. This historical richness and heritage diversity allowed the M'zab Valley region to be classified within the National Heritage in 1971. In 1982, it became UNESCO World Heritage registered as an outstanding example of a traditional human settlement that represents an important interchange of human values by their original architecture, urban planning, and interacting with the desert environment and Islamic Ibadis culture remaining unchanged to the present day [1,2].

From 2008, Algeria is vividly revitalizing domestic and international touristic activity. Currently, the country is seeking to promote tourism through numerous programs and development plans with a horizon in 2030 [3]. The region of Ghardaia has an extremely varied tourist potential. It is considered to be an open-air natural park of palm groves and oases, and also renowned with ancient millennium fortified cities and antiquities from prehistoric times, which gives it a prominent position within the strategy of tourism development [4,5,6]. These archaeological, architectural, environmental, historical, cultural and funeral sites are important ingredients for the development of sustainable tourism that respects the customs and traditions of the region and provides wealth for the local economy. The area is also famous for a series of active traditional markets and handicraft products (rugs, wool clothes, etc.) that is a factor to attract tourists from everywhere [4,7]. Recently, it became essential to exploit local heritage properly that can be a factor to preserve it.

During our research of Ghardaia, it became evident that the interest of local people in their settlement's revitalization is the way of tourism development. Local communities of fortified cities with the leading role of Al'umana, a traditional council of wise people, established a tourist association for each fortified city (ksar). Local volunteers organize regular tours inside the ksar and the oasis for the visitors to encourage the tourism and introduce the natural and cultural heritage of the region. We have investigated the revitalization and touristic activities of two settlements – Ghardaia and Bni Isguen – who acted nearly equally by creating “Tourist Orientation Association Your Ghardaia” and “Office of Tourism and Development Beni Isguen” accordingly (Fig. 3).

As a tourist, you must respect the sanctity and laws of the ancient settlement, take a local tour guide for your tour, and respect the visit hours. You also need to be modestly dressed and avoid photographing passers-by and smoking inside the ksar. It is not allowed for tourists to stay inside the ramparts of the ancient settlement. The Mozabites prefer to preserve the privacy of their daily life and usually allow nobody from outside to enter the ksar further than a marked place located near the entrance gate without the supervision of a local person. All touristic infrastructure is located at the extensive city developed outside of the ramparts.

The settlement tour usually takes one hour. It starts from the marketplace (Fig. 3 right) and goes on to the top of the ksar where the mosque is located; passing through the narrow alleys with mud dwellings adjacent and then ends at the museified houses exposing the internal life of the Mozabite society.

There are also some organized tours to the oasis while the visitors can explore the palm grove, summer dwellings of Mozabites, and the traditional irrigation system of the settlement. During the tours, the guide gives a historical overview of Mozabite architecture, culture, and traditions, and answers all the tourists' questions as well. Volunteer tour guides as a rule are highly educated persons, sometimes even members of Al'umana local wise council, who ensured the necessity of revitalization of the tourism sector in the M'zab region. They emphasized the interest of the Mozabite community in tourism development and their openness to tourists from all over the world. They also have a lot of annual events and traditional celebrations that attract tourists. The most significant of them are the Feast of Al-Zarbeya (carpets), Feast of Mehri, the Month of Heritage, Amazing New Year, etc.

Left: Office of Tourism and Development Beni Isguen. Right: traditional marketplace at ksar Ghardaia (photos by the authors).

3. KRYVORIVNIA CASE

Kryvorivnia is a picturesque Carpathian mountain village located in the Ivano-Frankivsk region of Ukraine, not far from Verkhovyna district center on the bank of the Black Cheremosh River. The settlement has an extended urban structure of separated groups of dwellings which is traditional for this region. The village was firstly mentioned in written sources at the beginning of the 18th century, but it is obvious that the settlement existed far earlier. From the 19th century, the village has become famous as a popular natural resort and artistic hub often being visited by famous writers, artists and actors of the time. At the end of the 19th – beginning of the 20th century such famous personalities of culture as Ukrainian writers Ivan Franko, Lesya Ukrainka, Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky and historian Mykhailo Hrushevsky temporarily lived or visited there, as well as Russian theatrical performers Konstantin Stanislavski, Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko and others [8]. Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, who lived there in 1910, in 1911 wrote there his famous novel “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors” (known in English as “Wild Horses of Fire”), a mystical and tragic love story based on Kryvorivnia's local Hutsul people's life, traditions and legends. In 1964, the famous Georgian-Armenian filmmaker Sergei Parajanov filmed this novel also using Kryvorivnia as the main scene for filming [8].

Having such interesting artistic history, Kryvorivnia village, until the end of the 20th century, after the hard time of several wars, remained just one of several picturesque but quite ordinary and not so rich villages of the Ukrainian Carpathian region. This mountain forestland is historical territory of the Hutsuls, an ethnic subgroup of Ukrainians that due to settlement on the territory of deep mountains almost fully preserved its historic originality, including unique dialect of Ukrainian language, outstanding wooden architecture style, national clothes and crafts, folklore, traditions, festivals, and so on.

The process of Kryvorivnia popularization and revitalization started there at the very end of the 20th century, initiated by efforts of the local community and greatly influenced by Ivan Rybaruk, a new priest of the local ancient wooden church who obtained parish there in 1995. Currently, Kryvorivnia has recovered of local community and religious life with famous folk festivals. The most popular cycle of local festivals is connected to Christmas celebrations in wintertime. There survived ancient local folklore traditions of Christmas songs as well as musicians' performances playing traditional violins and so called trembita – extremely long Hutsul's trumpets made of “thunder-wood” – the trunks of the trees heated by the lightning. Especially spectacular is the festival of Baptism celebration taking place on 19 January and accompanied by the entire village praying at the bank of Cheremosh River with installed in the water a big decorated cross, carved out from river ice. At the beginning of June takes place “Sheep sending to poloninas” festival. This is a symbolic day when local people are sending their sheep to high mountain pastures (so called poloninas) for all summer grazing. All these festivals are usually events of all villagers' participation attracting many spectators from all over Ukraine and abroad (Fig. 4).

An interesting aspect of Kryvorivnia's community is its multicultural vector of development, tolerant attitude to religious, national and lifestyle diversity. Praying on big Christian festivals there goes on with the participation of several priests: representatives of the Orthodox, Catholic and Greek Catholic Churches. There are also no restrictions for any other religious representatives to visit and pray in the church, everybody is sincerely welcomed.

Kryvorivnia's famous Christmas festivals (photos by the authors).

Wooden Maria's Nativity Church of Kryvorivnia. Left: outside appearance before the restoration at the end of 2010. Center: outside appearance after the restoration. Right: the painted interior (photos by the authors).

The center of these events is the ancient painted inside wooden Maria's Nativity Church of Kryvorivnia (Fig. 5). It was built in the Kryvorivnia area probably in the 17th century and then transferred to the current location up the hill at the center of the village in 1719 [9]. The Maria's Nativity Church is one of the best regional examples of the Hutsul architectural style of a log-construction church erected over cross elevation with one central opened to the interior dome-tower of “octagon-on-cube” type that shows the possibility of its historic connection with Armenian sacral architecture [10,11,12]. The church is designated as National Cultural Property, but despite this, from the third part of the 20th century the exterior of the church was covered with ugly metal leafs, the cheap but harmful way of damaged roofing repair for wooden constructions. At the end of 2010, due to priest Ivan Rybaruk and community efforts, the church was restored by local carpenters returning it to its original exterior of chopped wooden planks covering the roofing and walls as traditional rain prevention method.

Traditional skills passed from father-to-son preserved by families of local carpenters and other artisans are an interesting point of the village life. There are still erecting new wooden dwellings using old building traditions, compositional structures and “evil defense” pre-Christian customs. In addition, there are still a lot of ancient mountain dwellings and outbuildings kept from the 19th century and even earlier. There are also still flourishing old-fashioned professions, crafts and arts such as sheep breeding, cheese making, clothes and carpet making, wood carving, egg painting (pysanka art), and others. So no wonder that Kryvorivnia became famous as a green-tourism center attracting people with its picturesque mountain sceneries and hiking routs. There is mostly developing family tourism with no big touristic groups. The tourists usually stay at local peoples' dwellings or small house-hotels using local food facilities and tightly communicating with the villagers.

Another point of Kryvorivnia revitalization reality is a vide museification activity starting from the middle of the 20th century when in 1954 the first memorial museum of writer Ivan Franko was opened there. Currently, Kryvorivnia has 7 museums of different types including local ethnographic and historic museums and the original museum “Didova Apteka” (“My grandfather's pharmacy”) organized by the local Zelenchuk family to commemorate their grandfather who was a famous herb-healer of the village [13]. There is also a memorial museum of the local female ethnographer, writer, artist and photographer Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit (1927–1998) who left behind a great artistic and cultural heritage now carefully classified and exhibited [14]. Another interesting museum is the historical (probably built at the beginning of the 19th century) Hutsul-type wooden rural dwelling complex with closed inner yard (so-called hrajda). The local community together with priest Ivan Rybaruk and his family also widely popularize Kryvorivnia to other Ukrainians organizing outside concerts, seminars and exhibitions. Thus, Kryvorivnia became popular among domestic and foreign cultural figures. As such, Kryvorivnia has now fully reobtained its historic significance as artistic hub and “cultural capital” of the Carpathians.

4. COMPARING THE CASES

Both analyzed cases are examples of traditional sustainable settlements deeply integrated with surrounding nature, the culture of both settlements characterized by a strong religious component. Both settlements almost fully preserve the natural environment, local traditional architecture, customs, agriculture, traditions, crafts and way of living. Their revitalization is historically based on the conscious activity of strong local communities [15], introducing the diversity of settlement vitalization ways and touristic facilities development.

At the same time, the initial circumstances as well as the character of revitalization and touristic activity of M'zab and Kryvorivnia are different. Mostly, the M'zab Valley's settlements could be considered more self-sufficient and tightly preserving their identity, while the habitants of Kryvorivnia are much more integrated into the modern world.

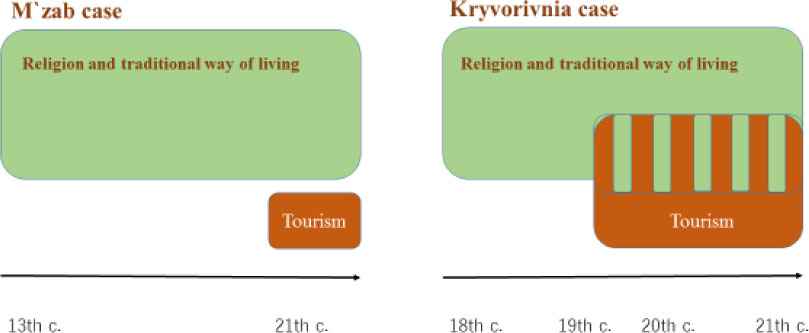

Both settlements are characterized by great hospitality to guests, but in the case of M'zab we can observe the tendency to separate real-life settlement from its touristic component allowing the guest guided by local volunteers to only observe local life but not to participate in it. This shows the intention of the local community to protect its private life and customs from the tourists (Fig. 6). The leading role of the revitalization process of M'zab belongs to Al'umana, a traditional council of the local community's wise people, creating guide volunteer organizations to develop the local tourism.

At the same time, in Kryvorivnia the guests and tourist are fully integrated usually settling inside the village and widely participating in its daily life, traditional festivals, religious events, etc. (Fig. 6). The important role there belongs to religion that due to the personality of the local priest became a driving force of village revitalization process concentrating the community around the ancient wooden church.

Besides cultural and historic reasons, such differences can be explained by the length of experience of these activities which is different for the two analyzed cases. As shown in Fig. 6, in the case of M'zab touristic activity started quite recently, while in Kryvorivnia presence of touristic facilities is already in some way traditional with more than a century of background.

Interaction between traditional life and touristic activity in the M'zab and Kryvorivnia cases (drawn by the authors).

5. CONCLUSION

Nowadays, traditional settlements survived mostly in specific geographic regions with natural conditions cutting them off from the rest of the world. They are often in hard-to-survive territories forming the sustainable ability of the human settlement to adapt and integrate deeply into nature or even being symbiotic with it. As such, historical settlements are able to preserve their identity only integrating with local natural surroundings. Namely, the traditional settlement cannot exist without surrounding nature that gives possibilities and at the same time the necessity to continue practicing local building techniques, crafts, agriculture, etc. At the same time, the preservation of this “status quo” in the modern world of globalization requires conscious efforts of the local community. Revitalization and touristic activities can be applied in different ways according to the local geography, history, culture, religion, customs and other characteristics of the settlement.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTION

The authors contributed to the results of the research in equal proportion. Galyna Shevtsova conducted the research of Ukrainian Kryvorivnia village. Nourel Houda Rezig conducted the research of Algerian M'zab Valley settlements. The introduction part of the article, the comparison analysis of the two researched cases, the illustrations and the conclusions are the result of the authors' equal collaboration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are deeply grateful to the “Tourist Orientation Association Your Ghardaia” and “Office of Tourism and Development Beni Isguen” of M'zab Valley and specifically to the local guides Mostafa Boughlousa and Hadjour Brahim, who significantly helped us with the field research and shared a lot of important supporting materials. The same is for Kryvorivnia village community and specifically for Ivan Rybaruk, the priest of the local Maria's Nativity wooden church, Oksana Rybaruk, Ivan Zelenchuk and other local volunteers.

REFERENCES

Cite This Article

TY - CONF AU - Galyna Shevtsova AU - Nourel Houda Rezig PY - 2023 DA - 2023/01/10 TI - Ancient Settlements With Traditional Ways of Living – Revitalization and Popularization Experience: Cases of M'zab Valley in Algeria and Kryvorivnia Village in Ukraine BT - Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Architecture: Heritage, Traditions and Innovations (AHTI 2022) PB - Athena Publishing SP - 177 EP - 184 SN - 2949-8937 UR - https://doi.org/10.55060/s.atssh.221230.023 DO - https://doi.org/10.55060/s.atssh.221230.023 ID - Shevtsova2023 ER -